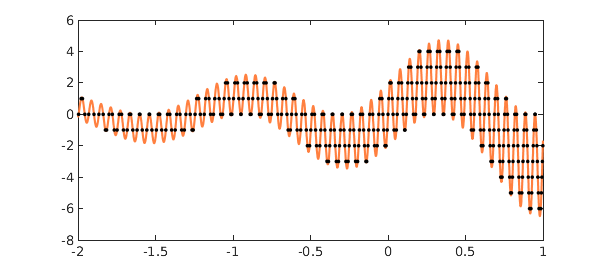

My essay "Six myths of polynomial interpolation and quadrature", reproduced as an appendix in [1], closes with an example that reminds one of a tiger's tail. Here with a few modifications is that example:

x = chebfun('x',[-2 1]);

CO = 'color'; orange = [1 .5 .25];

f = 2*exp(.5*x).*(sin(5*x) + sin(101*x));

roundf = round(f);

r = roots(f-roundf,'nojump');

hold off, plot(f,CO,orange), hold on

ylim([-8 6])

plot(r,f(r),'.k'), hold off

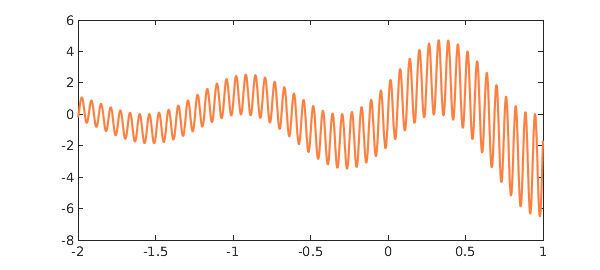

Let's look at what's going on here. First of all a chebfun $f$ is constructed:

plot(f,CO,orange) ylim([-8 6])

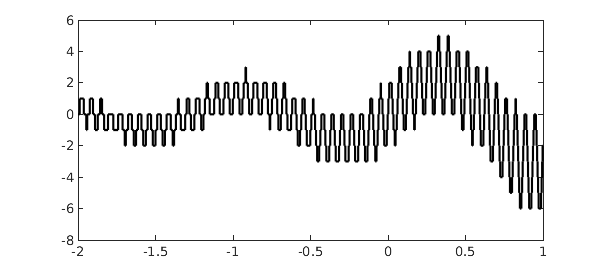

Then another chebfun is constructed consisting of $f$ rounded to integers:

plot(roundf,'k','jumpline','k') ylim([-8 6])

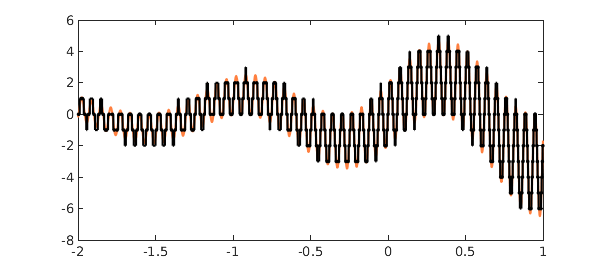

Superimposing the two curves yields a lot of intersections, which are computed by roots:

number_of_roots = length(r) plot(f,CO,orange), hold on plot(roundf,'k','jumpline','k') plot(r,f(r),'.k'), hold off

number_of_roots = 345

In [1], dots appear not only where $f$ is equal to an integer, but also where it is equal to a half-integer. In the present version of the tiger's tail, this effect has been eliminated by use of the 'nojump' flag in roots.

Reference

- L. N. Trefethen, Approximation Theory and Approximation Practice, Extended Edition, SIAM, 2019.